Professor Hatamura, who served as chairman of the Japanese government’s committee investigating the March 2011 accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, told the JAEC that “there is no such thing as absolute safety,” and that “when you think you have thought of everything, there will always be something you have not thought of.”

Moreover, he said, an overconcentration on disaster prevention would impede the development of measures to reduce the effects of the disaster, that is, minimizing the damage when an accident actually does occur.

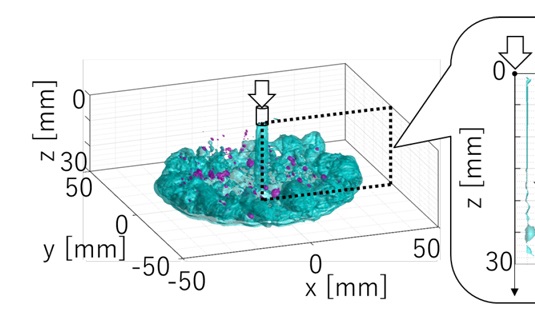

The professor proposed looking at the accident at Fukushima as a “single picture” in order to grasp the entirety of what happened. He said that a simulation should be conducted to reproduce the accident, identifying individual events, and analyzing how each of them developed.

The results, he added, should be reflected in future designs of nuclear power plants (NPPs), with accident response measures developed accordingly.

The professor also characterized the ongoing decontamination situation at Fukushima as merely “building temporary storage facilities until other temporary storage facilities could be built.” He said that such a plan was unrealistic, and called for its review.

The key, he said, was “not to gather and not to transport.” He introduced a method of “disposal at each spot, burial in deep holes,” which would involve scraping off the contaminated surface soil and covering it with clean soil.

According to Hatamura, if nuclear power continues to be used, we must assume that accidents will happen. He said that we should therefore make plans and take steps to minimize damage, conduct trial runs that are as realistic as possible, confirm the appropriateness of the original plans, further issue a decontamination plan, convey it to the residents, and obtain their understanding.

The professor also said that we must create a culture that allows us to recognize what is dangerous, openly discuss the dangers, and develop the human resources to respond to the unexpected.

Stating his own view that it takes as long as 200 years for enough failures to be experienced in any field for it to be understood, Hatamura noted that our experience with nuclear power so far has been only 60 years. Still, he added, we can shorten the “learning period” by incorporating experience and knowledge from other fields.

-013.jpg)