Sae Ochi, MD, MPH, PhD

Director of Internal Medicine, Soma Central Hospital, Fukushima

Clinical Research Fellow, MRC-HPA Centre for Environment and Health, Imperial College London, UK

Now that five years have elapsed since the earthquake and tsunami disaster of 2011, the gap between “Fukushima on the Web” and Fukushima in reality is growing ever larger.

Meeting and talking with the people in the Fukushima area—who are living their lives healthily and vigorously—I often log on to my personal computer in a joyful mood, but then get appalled at what I find there: a dark image of Fukushima being spread across the Web, swirling in conspiracy.

The picture of Fukushima that one finds in Internet searches is not the real Fukushima. Accordingly, it is impossible to carry out a paradigm shift about the subject on the Web. Today, when everyone in the world relies on search engines, I feel that it has become increasingly important to communicate a “recipe” by which information can transmit the truth.

Society Is Losing Its Power to Communicate

“The weakness of modern humans is their reading of newspapers, as what is written in the papers with relevance to oneself is generally a lie. Nonetheless, everyone believes things that are written in the papers about people. That’s the flaw of modern humans.”

Those words were voiced by Hideo Kobayashi (1902-83, Japanese author and literary critic) in an interview recorded in 1941, in wartime. In modern times, even more than then—an age when people got their information via newspapers and radio—I feel that such a tendency has become aggravated by the development of the Internet.

The Information Age Has Created Greater Remoteness

According to a spokesman for a nonprofit organization (NPO) in Minamisoma City in Fukushima Prefecture:

“The entire picture of Fukushima just doesn’t get transmitted. The statements of one person are focused upon as the ‘voice of the local people,’ making it impossible to relay the real situation, with its mixture of proponents and opponents, as well as those who say they ‘don’t know.’”

In modern society, whenever people want to find out something, they go to the Internet and conduct a search. With the development of search engines, it has thus become possible for all of us to rush, in a beeline fashion, toward precisely the information we are looking for; that is to say, we go directly toward the particular. However, on account of that, I think we are gradually getting fewer opportunities to get a comprehensive take on things, as opposed to what we would get in a textbook or a lecture.

Having acquired the particular without a knowledge of the general, people who conduct searches only get a hold of the type of information closely reflecting their prejudices, as they successively throw out other pieces of information that differ from their opinions. In other words, information about Fukushima ends up not getting to people who do not want to know about it, and those having a prejudiced view of Fukushima only rarely come across a “positive Fukushima.”

A Recipe for Information

The main problem today is that recipes for the interpretation of information have not developed as quickly as the explosive rate by which the amount of information itself has increased.

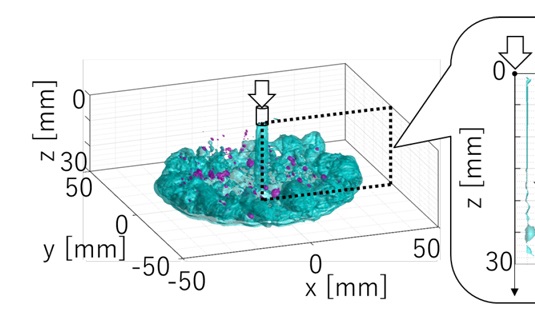

In discussions of [the incidence of] thyroid cancer [among Japanese children after Fukushima], some people raise this question: “If thyroid cancer today is supposed to be the result of [intensive] screening, how can you explain the fact that such cancer has been found in more than one hundred children [in the Fukushima area]?” At first, I was unable to understand it. To put it differently, although people have mentioned that the discovery of thyroid cancer in more than one hundred children might be the result of [intensive] screening [rather than representing an absolute increase], I thought that inverting the question rendered the whole thing rather incomprehensible.

Meanwhile, listening to various people talk, I came to the conclusion that perhaps they believe that it is improper to treat the term “screening effect”—a non-emotional term—as having equivalent value to the term “[the cancer of] one hundred children,” which is a shocking piece of information.

Granted, information is not the same thing as science. There is no obligation to always interpret all the information one has at hand scientifically and cold-heartedly. But when the data themselves are scientific, what needs to be told ends up not getting communicated at all unless it is first “prepared” or “cooked” using a scientific recipe, at the bare minimum.

In the case of Fukushima, in particular, I sense that there is a glut of misguided “information recipes” that prepare scientific information with ethics “stirred in,” as well as those that “season” ethical issues with scientific evidence.

That might stem from the failure of many specialists, including scientists, to relay the proper [information] recipes while focusing single-mindedly on communicating only information.

Correctness and Wisdom

After the March 2011 disaster, Mayor Hidekiyo Tachiya of Soma City has repeatedly stated, “Radiation ought not to be ‘correctly feared’ but rather ‘wisely avoided.” I feel that much of the information being transmitted in society today is devoted to just correctness and fear, without making an effort to also communicate wisdom and methods. Just relaying the correct numbers and statistics does not equate to communicating the truth. We have now reached the point, I think, where that point needs to be seriously reflected.

Information is not numbers. Even now, five years since the March 2011 disaster, information is a “living being” that has both color and temperature. I wish that the people living outside of Fukushima, also, would appreciate that.