Sae Ochi, MD, MPH, PhD

Lecturer, Department of Laboratory Medicine, The Jikei University Shchool of Medicine

Attending Physician, Soma Central Hospital

“I come from Soma City in Fukushima Prefecture.”

When using those words to introduce myself to others who live outside the prefecture, I am often confronted with various facial expressions that are hard to describe. Some people seem to be wondering to themselves if it is all right to smile, as they are worried that they might be viewed as being discriminatory. Meanwhile, others wonder whether it is OK to talk about radiation, even though that is what immediately comes to their minds [when they hear the name Fukushima]. Anyway, those are the sorts of expressions I see on the faces of people when I tell them where I am from, indicating their various concerns.

The feeling that some people get when thinking of Fukushima—that is, the thought that “I don’t know how to respond to unhappy people”—is deeply rooted, and goes beyond the aggressive negativity inherent in the image of discrimination and prejudice. That feeling is the cause for many people’s indifference, as they say they don’t want to get involved “because it is too troublesome.”

In reality, however, I truly feel that there are many happy people in Fukushima today. That happiness is something that qualitatively differs from just “living bravely” and “starting to notice small happy things on account of the big ‘unhappiness’ that occurred [namely, the giant earthquake and the reactor accident].”

These are some of the comments I have heard recently in Fukushima:

“I am happy that high school students’ laughter has returned to the Odaka area. I’d like to create a bookstore where such students can feel free to drop in.”

“We have all the things we need to live here in Fukushima, simply because we began to notice them once we evacuated. I want to tell various people about such wonderful things.”

“Now that major companies are abandoning Fukushima-made products owing to unfounded rumors, this is a big opportunity for our products to compete just on their good taste alone.”

Although my writing ability fails to fully convey what is going on, there are definitely people here in Fukushima with the extroverted type of ‘mental circuitry’ that leads them to actively find happiness.

There is a nonprofit organization (NPO) in Fukushima called the “Soma Follower Team,” which has continued to support children mentally and spiritually almost from the moment that the earthquake struck in 2011. According to staff members, having experienced the earthquake disaster has not necessarily proved to have been only a negative factor in people’s lives.

One person told me, “Some children who used to be estranged from their families before the earthquake came to view them more objectively once they started living apart from them after the disaster. Though some of my students had been quite irritable before, they came to take a hard look at themselves and were able to become more positive.”

It is a well-known fact that the incidence of PTSD—post-traumatic stress disorder—goes up after major disasters. However, on the other hand, there also seems to be a phenomenon known as PTG, or post-traumatic growth, referring to the way that people’s minds and their relationships with others tends actually to change in a positive direction after recovering from a disaster.

In the past six years, ever since the earthquake, many people in Fukushima have continued to ask themselves what happiness is, and how to become happy. Naturally, there are also many people who still cannot overcome their sorrows. Nevertheless, not all the people who have had sad experiences are necessarily unhappy. That is what I think every time I meet someone who derives deeper fun or pleasure (tanoshimi) utilizing the giant “stain” of the earthquake disaster. It is precisely such a “power of happiness” that is the positive legacy that can be gained from post-quake Fukushima today, especially considering the malaise that has descended upon the country in recent years.

In such a case, why, then, does that powerful image of Fukushima fail to get transmitted to the outside? Let me say—with a bit of self-recrimination as well—that I believe that it is due to the poverty of “happiness” among those experts who are conveying what is happening here.

The other day, the president of a company known as Shikumi Design told me, “You can say ‘Wow!’ only once, but can say ‘This is fun!’ countless times.” Truly, those words can be applied to Fukushima today. Many written descriptions about the extraordinary nature of the experiences of people [during the earthquake] here are interesting when read the first time, but no one wants to read them again. The fact that the subsequent story of Fukushima, about which one wants to read repeatedly, does not get told may be the result of the fact that we are captives of that moment on March 11, 2011, and still are searching solely for the ‘Wow!’”

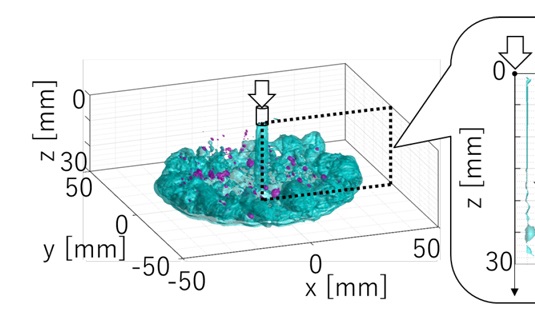

It is definitely fun to learn from the discussions and debates about what is happening now in Fukushima, in such areas as decommissioning technology, deep-sea protection, and regional revitalization. What I mean by “fun” here is not a sense of sheer pleasure or enjoyment, but rather the interesting kind of “fun” that refers to the feeling that one gets when one’s intellectual curiosity and deep thoughts are stimulated. Such “interestingness” cannot be achieved through events; rather, the attraction of Fukushima today lies in in the dreams, journeys and thoughts created through trial and error.

However, that cannot be communicated by people on the transmitting side unless they have developed the sensitivity to realize such fun as well as having the requisite writing ability. Considering that, the increased indifference to what is happening in Fukushima may partially be the responsibility of us experts, who still lack the adequate kind of thinking and verbal ability that will attract people.

The moment that people hear the word “Fukushima,” their eyes sparkle and they want to learn all they can about it—such is the image of Fukushima that I hope to convey from now on. That is my challenge.