Earlier that morning, at around 3:00 a.m., the unit carried out a temporary grid connection (“initial synchronization”), raising generator output to approximately 20% of rated electrical output (about 270 MW) to confirm operating conditions. It was then disconnected from the grid and output was reduced to 0%. As part of checks on the turbine protection system, turbine speed was increased above rated speed to verify that the turbine would automatically trip. After confirming this function, the generator was reconnected to the grid (final synchronization), and output was gradually increased to approximately 50% of rated electrical output (about 680 MW).

The company plans to conduct an interim shutdown once between February 20 and the latter part of the month, after which it will resume the reactor startup and pressure-raising process. During this interim shutdown, various data obtained during the initial power ascension tests (20–50%) and overall plant behavior will be evaluated and confirmed in detail. The inspections will focus mainly on the turbine system, checking temperature and pressure changes during startup as well as vibrations associated with equipment operation, to confirm that there are no abnormalities in equipment or piping.

After confirming safety through these evaluations, the plant will proceed to the restart process. Following restart, reactor output will be raised step by step to confirm stable continuous operation. A comprehensive load performance test is scheduled for March 18, and upon successful completion, the unit will enter commercial operation.

In response to the start of power generation at Unit 6, Japan Atomic Industrial Forum Chairman MIMURA Akio issued a statement saying he “wholeheartedly welcomes” the development. He expressed respect for the efforts of all those who have worked toward the restart over the approximately 14 years leading up to this point, and conveyed deep appreciation to Niigata Prefecture, Kashiwazaki City, Kariwa Village, and local residents for their understanding and decisions.

Chairman Mimura noted that the restart of the Kashiwazaki Kariwa-6 will enhance the stability of electricity supply and make a significant contribution to strengthening Japan’s energy supply resilience by mitigating fossil fuel procurement risks and price volatility. He emphasized that its significance is particularly great in eastern Japan, including the Tokyo metropolitan area, where securing supply reserve capacity remains a challenge.

Looking to the medium and long term, he stressed that achieving stable supply from economically competitive decarbonized power sources amid anticipated growth in electricity demand will form a foundation supporting Japan’s economic growth and international competitiveness. He added that the most important elements in the use of nuclear energy are ensuring safety and maintaining the trust of host communities. He expressed his expectation that TEPCO will steadily advance efforts such as strengthening governance and contributing to regional economies, continue dialogue with local communities, and work to ensure safety and reassurance while promoting regional revitalization.

He also stated that the nuclear industry as a whole will continue to make continuous efforts to ensure high levels of safety and quality in order to meet society’s demand for stable supplies of affordable decarbonized electricity.

-013.jpg)

-049.jpg)

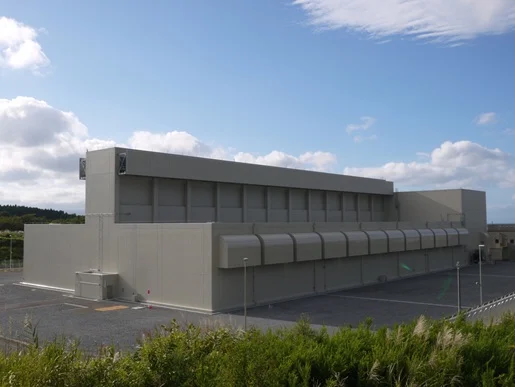

.jpg)