At the Stage to Proceed Systematically and Independently

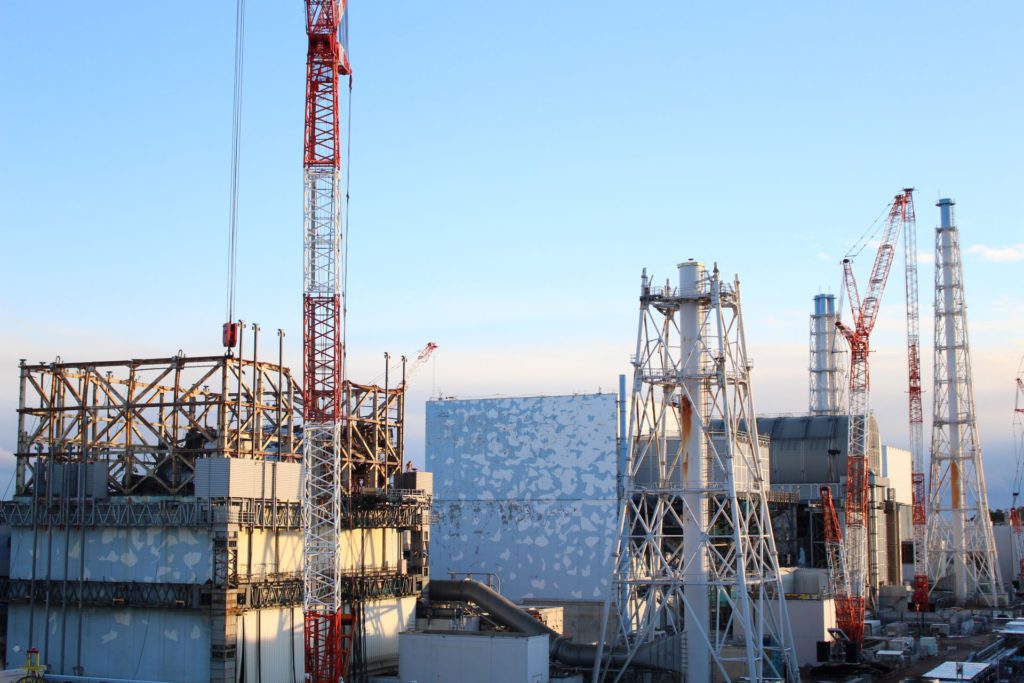

We interviewed Akira Ono, Chief Decommissioning Officer (CDO) at TEPCO, responsible for decommissioning and contaminated-water issues at the Fukushima Daiichi NPPs. We asked him about the company’s activities, the current status of the decommissioning work, and what to expect from now on. Ono is in charge of the decommissioning site on the front line, and says, “The environment has improved to the extent that decommissioning can be carried out as a systematic project with a planned schedule.” Looking ahead, he adds, for the sake of a safe, steady effort carried out over many years, that “we will also have to change.” He emphasized that, as the operator responsible for the project, TEPCO is fully committed to systematic, independent activities, including the issuance of the Mid-and-Long-Term Decommissioning Action Plan 2020.

– Would you tell us frankly what you think now, exactly one decade since the Fukushima Daiichi accident? Has decommissioning made progress according to the roadmap, and what are the current issues and future prospects?

Ono: At the time of the accident, I was assigned to TEPCO’s Tsurumi Branch in Kanagawa Prefecture. Immediately afterward, I worked on planned power outages. Nine months after the accident, I returned to Fukushima Daiichi. In June 2013, I took charge of the site as the site director of the station.

At that time, including the three years I was general manager, various problems arose every day. There were piles of issues to be resolved quickly, and I remember that I had no room to think ahead. I just physically moved around, responding to whatever the situation was.

Looking back on the past decade, an environment is now in place where we will be able to make progress in decommissioning in a project-like manner, calmly, looking clearly at what things will be like ahead as we move forward.

In that respect, things have changed greatly since the time when I was general manager. In the course of the work, the roadmap has been revised five times. Still, decommissioning at Fukushima Daiichi itself has made steady progress.

Particularly in regard to contaminated water, the volume of water was increasing by 500 cubic meters per day at the beginning; now it is less than 150 cubic meters per day. Originally, there was water in the turbine buildings, as well as in the reactor buildings, but it has now been completely removed from the turbine buildings.

Overall, contaminated water countermeasures and the removal of the nuclear fuel have generally been carried out as planned.

On the other hand, the removal of the fuel debris is the major issue, and I think that we will have to work on it quite patiently. Yet, we have ascertained very well the conditions of the sites, and will address them from now on, according to the roadmap.

– You led the decommissioning work at Fukushima Daiichi as general manager from 2013 to 2016, and have been CDO of the Decommissioning Engineering Company since 2018. Personally, what has made you the happiest, and what did you find hardest?

Ono: Honestly, most things were hard when I was general manager. The worst experience was the loss of three workers. Now, the work environment has been improved so much that such human accidents can be avoided. It is incredibly painful to think that there were victims among those who were working so hard in such difficult conditions.

At the same time, I was the happiest when personally being able to see the progress of the work. Let me give you an example. The fuel removal at Unit 4 was completed in 2014. I had watched the progress there since the stage of removal of debris from the reactor building’s operations floor. The site changed daily, and conditions steadily got better as work shifted to removal of fuel. During only those few years, some 1,500 fuel assemblies were removed safely—a visible manifestation of progress in the decommissioning effort. I felt rewarded, and it was indeed a happy event.

After returning to Fukushima Daiichi as CDO, I was gratified when dismantling of the exhaust stack for Units 1 and 2 ended in 2020. When fuel removal at Unit 3 experienced a series of problems at the beginning, I was aware that decommissioning would be quite difficult. That is one of my strongest memories. At the same time, I recognized the need to respond properly to quality issues that had been clearly shown. I will reflect that in our activities from now on.

Let me add one more thing. After serving as general manager of Fukushima Daiichi, I was at the Nuclear Damage Compensation and Decommissioning Facilitation Corporation (NDF) for one year and nine months. That was an extremely valuable opportunity for me to have a third-party look at the decommissioning worksite. It also gave me the time to consider how the decommissioning should be carried out afterward, and to understand how various external people looked at the site and at TEPCO.

With those experiences, when I became CDO of the Fukushima Daiichi Decontamination & Decommissioning Engineering Company, I talked to the employees about the need to carry out the work systematically. We have gone through stages in the decommissioning process. Our implementation must be systematic, premised on being safe and consistent.

In a way, I was calling on them to think about the need to change. There is a popular Chinese saying that goes, “When you are in real trouble, you will find a way out.” The original saying, though, is somewhat longer, saying, “When you are in real trouble, you must change, and when you change, you will find a way out.” In short, I thought that we would have to change at some point.

So, taking every opportunity, I talked to the employees to instill a sense in them that, to continue for the long term, for three decades, we would have to change ourselves in places and at times. And what I kept saying then has now been formulated into the Mid-and-Long-Term Decommissioning Action Plan 2020, released almost a year ago on March 27, 2020.

At the beginning, some employees were plainly perplexed by the difference between an action plan and a roadmap. A roadmap reflects only milestones in our process—things that we should keep in mind—to guide ourselves in how to move forward. I explained it that way, and gave instructions to make the plan. The employees took up the challenges, and our results assumed visible form. It was a major accomplishment, and I was incredibly happy about it.

Keeping a Close Eye on the Future,

Efforts Are Continuing to Improve Safety and Quality

– The national government is considering ways to dispose of the treated water as a result of decommissioning. How do you see this issue concerning that point? Also, what would be the impact be, do you think, of the release of contaminated water on ecological systems and human health? After the government decides how to dispose of it, how will TEPCO approach the task?

Ono: The government will make its decision after considering the views and thoughts of various specialists and related parties. We will certainly then dispose of the water based on the policy that is decided upon. At that stage, we will engage with relevant parties and listen to their opinions sincerely.

Many people are concerned about the disposal of the water from a societal viewpoint, which sometimes reflect unfounded fears and rumors. I understand that the focus of deliberations by the governmental committee is shifting to that point now. Keeping that in mind, we will have to be sure to disseminate information in a manner that does not cause misunderstanding.

For example, when people hear about tritium, they may not immediately understand what that is. It is important that the information we provide includes basic information on tritium.

We recognize that providing information is itself an important measure to prevent unfounded fears and rumors, and will make sure to do so properly. If, nevertheless, misconceptions arise, it is TEPCO’s responsibility to deal with them. That is an issue that the company will work on after the government presents its decision.

Because a disposal method for the treated water has yet to be decided, what I can say is rather limited. In the report released last year by the Subcommittee on Handling of the ALPS Treated Water, two candidate methods were identified: offshore release and vapor release. Both methods have been used successfully overseas. Speaking from a technological point of view, I recognize that each is a means that can adequately ensure safety.

From now on, based on the national policy, we will squarely engage all related parties and decide on a specific method. We will respond in a broad range of areas, including with necessary facilities and equipment, providing information, and, if they arise, dealing with any unfounded fears and rumors.

– Questions about the accident are steadily being answered. How are the lessons learned being reflected in improvements to the safety of NPPs worldwide? Can you say that a similar accident would never happen again?

Ono: That the accident occurred was indeed a failure, and we are responsible for it. The mechanism of post-accident developments remains unclear, and we are working to put together the entire picture. Even a decade later, there is still residue at the accident site at Fukushima Daiichi that can contribute to verifying the cause. We are working on their preservation.

Having resumed various investigations two years ago, the Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA) of Japan , too, is focused on the site to see what it can still contribute to understanding the cause of the accident. We are cooperating with them. It is our responsibility to investigate and analyze matters while considering how we can contribute to improvement of nuclear safety. It is also important to share whatever can be obtained, not only domestically but also with the entire world, and utilize it to improve nuclear safety.

Based on the lessons learned from the accident, various measures have been implemented both domestically and at overseas NPPs. From that, I believe an accident like what occurred at Fukushima Daiichi is unlikely to occur again. But I cannot say so absolutely.

At worksites, our motto is: “Safety: Better today than yesterday. Better tomorrow than today.” Most importantly, we understand that there is no limit to safety. We strive continually to improve, learning not only from Fukushima Daiichi but taking every broader opportunity. I think that it is particularly important to move forward with that mental attitude.

The Key to Obtaining Public Confidence Is Not Causing Any More Problems

– Decommissioning goes on, but for it to be successful, the development of related technology is a must. Please give us your thoughts on any such innovative technology.

Ono: The primary areas requiring technological innovation in the case of Fukushima Daiichi are remotely controlled operations and robots. In addition, analytical techniques will be increasingly important. A substantial part of the technology necessary for decommissioning at Fukushima Daiichi will likely be new, innovative technology.

That does not, of course, mean that completely new technology is needed for everything. Taking remote-control technology as an example, extensive developments have occurred overseas. We will improve on existing technology or complement it, combining the existing with the new.

One of the main reasons for issuing the Mid-and-Long-Term Decommissioning Action Plan 2020 was to clarify when and what technology will be necessary. That is useful in the sense that we can figure out when we should start development of necessary technology.

Up to now, for example, the national government has developed technology related to fuel debris as a state project. The result has been that we have, to some extent, been dependent on the government. From now on, as an operator responsible for decommissioning, we will take the initiative in developing technology and attempt to match those development efforts to on-site needs.

We made the Mid-and-Long-Term Decommissioning Action Plan 2020 when we reached a new stage in the decommissioning. Accordingly, we also undertook to make major organizational changes.

In addition to the reorganization, we will have to make sure our systems are firmly rooted and effective.

In terms of quality management, some facilities at Fukushima Daiichi were created hastily, out of necessity, after the accident. If asked whether we did that while thinking about what it would be like three decade hence, well, we did not, and, as a result, problems are occurring now. From the beginning, it was probably inevitable that, at a certain point, everything would have to be switched over to facilities that could be used for two or three more decades. I think that we have reached that stage now.

– Decommissioning will continue for many years, and the understanding of local people, including those living in Hama-Dori, is essential to that. What will you do to help them—not just the returnees to Fukushima, but those still living elsewhere as evacuees—in understanding the realities of decommissioning, and to feel secure?

Ono: The most essential thing to be done is to obtain the confidence of the local people is not to cause any further problems. It is especially important to improve the environment so as to free people from worry.

Efforts to improve quality are, as I said, an area in which we will have to continue to strive. Those improvements, together with those in safety, will reduce the number of problems and other concerns. In that process, people will naturally come to trust us if safety and security are both improved.

And in all of that, the dissemination of information is a key element. It is particularly important to convey both the bad and good openly.

When we dismantled the exhaust stack for Units 1 and 2 last year, we asked local companies to do the actual work. We realized that it was important to carry out the decommissioning in close cooperation with local industries, so that the various technologies could take root in the region of Hama-Dori and be of value after the decommissioning is completed. I hope to continue to utilize the decommissioning project in that way.

Together with last year’s release of the Mid-and-Long-Term Decommissioning Action Plan 2020, TEPCO announced its promise to Fukushima that “reconstruction and decommissioning will proceed together.” That reflected our pledge, stated in the decommissioning roadmap, to carry out reconstruction and decommissioning concurrently. We want to create an environment in which we can move forward with decommissioning hand in hand with the people of Fukushima. I reiterate our determination to do that.